Poaching threatens the African Green Pigeons in Semuliki National Park

Despite decline in arrests of poachers since Covid-19, few arrests end in prosecutions

By Alex Baluku, Richard Drasmaku, and Polite Musa

By Alex Baluku, Richard Drasmaku, and Polite Musa

The sight of African green pigeons gracefully soaring through the rugged valleys of Semuliki National Park has long been a delight for tourists.

However, the conservation of these birds is being challenged by poaching as the local communities surrounding the national park view them as a means of livelihood.

The African green pigeon is distinguished by its yellowish green plumage and pointed tail feathers.

It finds its habitat in Semuliki National Park, a lowland tropical forest tucked away in the remote western flank of Uganda.

The park’s unique setting often makes visitors feel as though they have ventured into Congo’s Ituri rain forest rather than the East African savanna.

As these birds traverse the open plains of the Sempaya and Rwakasenyi areas in search of saline soils, they frequently fall victim to the nets set by local poachers.

This unfortunate situation unfolds despite the supposed protection provided by the Uganda Wildlife Authority, which hails Semuliki National Park as a “true birders’ haven.” An enforcement officer at Semuliki National Park who only identified herself as Christine, says the birds attract visitors from around the world who are eager to venture outside their daily routines, armed with cameras and binoculars, to observe and appreciate these magnificent birds.

Beautiful African green pigeon attract visitors from around the world

Though not listed among threatened species, the pigeon are birds without boundaries. They fly all over the African continent looking for food. As they feed on fruits, they disperse seeds along their international journeys, which grow and contribute to local ecological systems.

However, the sacks of carcasses of the birds traded in bustling markets like Bundibugyo and other districts surrounding the park, especially during the dry season, paint a grim picture of a bloody episode unfolding within the national park’s boundaries. Despite a decline in arrests of bird poachers in the last two years, very few arrests of poachers end in prosecution – warranting further attention and action to conserve the birds, our investigation finds.

UWA Law Enforcement Manager Miss Kasumba Margret holding the only bird found alive among very many pilled in a sack confiscated from a poacher at Semuliki National Park head office.

The conservation challenge

Despite their ecological importance, the pigeons are at high risk from poachers in Semuliki National Park.

The Batuku, Babira, Batooro, Bamba, Bavaluma, and Bakonzo communities residing in Bundibugyo and Ntoroko districts consider the African green pigeon a local delicacy.

This cultural preference has fueled the demand for the birds, exacerbating poaching.

Also, according to Godfrey Baryesiima, Warden in-charge Semuliki national park, the birds tend to gather in large numbers when there is an abundance of food, particularly ripe ficus tree fruits.

He says that once a few pigeons spot the fruits, they communicate their findings to the main flock, resulting in a substantial influx of birds to that location. Unfortunately, this behavior makes them vulnerable to bird trappers and poachers.

Baryesima revealed that the trapping and poaching of African green pigeons primarily occurs in the Sempaya and Rwakasenyi areas in the northern part of the park.

“These areas consist mostly of grassland, connecting to Semliki flats, Lake Albert, and the Semliki Wildlife Reserve, extending up to Murchison Falls,” Baryesiima explains.

He added that the Sempaya and Rwakasenyi environs have salty soil, attracting the pigeons during the dry season. Poachers then take advantage of this behavior by identifying the gathering spots and setting up nets within the park.

“The open grounds where the birds congregate appear inviting to the pigeons, as they are suitable feeding areas. However, they end up entangled in the nets set by the poachers, inadvertently trapping themselves.” Baryesiima explains that poachers often keep a few birds alive in the nets as bait to attract more birds.

He said that when the pigeons see their trapped companions on the ground, they assume it is a feeding area and descend in large numbers, unknowingly falling victim to the traps.

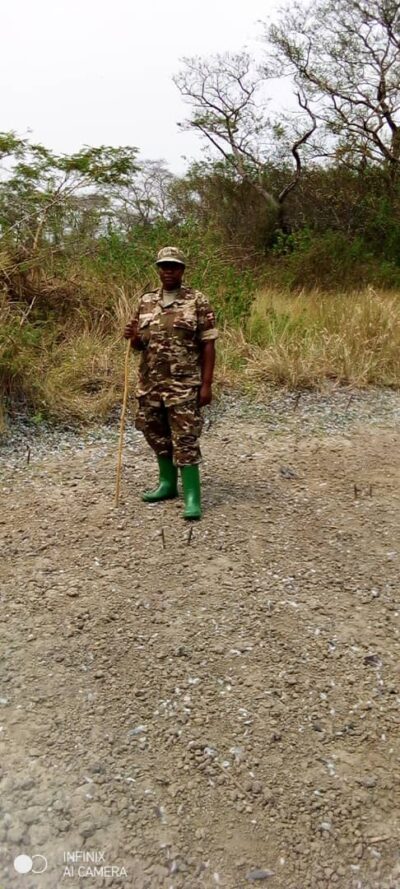

A ranger standing at one of the cleared grounds in Rwakasenyi after removing and confiscating the nets.(Nail like objects are pinned by poachers to help in holding the nets from being taken by wind)

A ranger standing at one of the cleared grounds in Rwakasenyi after removing and confiscating the nets.(Nail like objects are pinned by poachers to help in holding the nets from being taken by wind)

Covid-19 spike in pigeon poaching

An analysis of the statistics from the Uganda Wildlife Authority shows that thousands of illegal activities related to poaching of the African green pigeons were registered between 2018 and 2023.

Confiscation of trapping nets, recoveries of pigeon carcasses, and arrests of poachers reached a high in 2020/2021, and steadily dropped over the next two years.

Rangers arrested 189 bird poachers from the 2018/2019 financial year to 2022/2023 financial year. Of these arrests, the highest number (50) were apprehended in the 2021/2022 financial year, when the rangers also recovered 16 carcasses of the African green pigeons and 766 trapping nets.

Baryesiima attributes this spike to the socioeconomic hardships caused by the Covid-19 pandemic and the accompanying lock down, which he asserts forced many people to turn to the park for bird hunting to earn a living.

“The scale of the poaching problem is disheartening,” Baryesiima says, emphasizing that the arrests and recoveries shown in the data is only a fraction of what is happening in the national park.

Poachers typically trap 10 to 30 birds at a time, retaining some as live bait for further trapping, according to one poacher who asked to remain anonymous to protect his identity.

This illegal trade in wildlife is driven by the demand for the birds’ meat. The trapped birds are then sold in sacks at various nearby trading centers, including Karugutu, Nyahuka, Bundibugyo, and Burondo. Others are transported to neighboring districts of Ntoroko, Kabarole and Kasese.

A woman displaying African green pigeon at one of the selling centers. (the selling centers though hidden are known by the locals)

A woman displaying African green pigeon at one of the selling centers. (the selling centers though hidden are known by the locals)

Fraha Kasfa, a businesswoman involved in the cocoa trade at Burondo Central Trading Center, acknowledges that traders frequently check the selling centers for pigeons.

She says in some cases, poachers even go from house to house to find customers for the birds.

Kasfa attributes the flourishing of this illegal trade to the belief that African green pigeons possess nutritional benefits, particularly for improving blood concentration in children. Furthermore, there is a perception that the birds’ soup possesses curative properties against certain illnesses.

Several poachers from Bulondo and Lwamabaale, who wished to remain anonymous de to fears of retribution from their colleagues, attested that they have established a network of informants stationed at strategic points around the national park to help ensure their safety. These informants alert them when park rangers are patrolling, allowing the poachers to evade arrests.

Within their poaching groups, there are strict rules against stealing each other’s nets, and severe penalties are imposed on individuals caught stealing or found in possession of stolen nets. When there is an abundance of captured birds, the price drops significantly, as each poacher sets their own price to quickly sell off their stock.

The ongoing rainy season is currently disrupting their business, the poachers said.

Few arrests face prosecution

Despite the continuing poaching issues, warden in-charge Semuliki national park Godfrey Baryesiima indicates that there has been a general reduction in the pressure on the African green pigeon following the lifting of the pandemic lock down. He attributes the reduction in crime also to increased law enforcement efforts.

UWA improved its operations by employing spot checks and ground patrols by rangers to identify and confiscate nets set by poachers, according to Baryeisiima.

Offenders are apprehended and prosecuted. Those who face legal action may receive punishments such as jail sentences between four to seven years imprisonment.

Baryesiima showing journalists nets confiscated during enforcement

However, information from the police investigations directorate of Bundibugyo district shows that most of the arrested suspects go Scot free. Only about 11 percent of people arrested between the financial years 2018/2019 and 2022/2023 were prosecuted, police statistics show.

“Some arrested individuals receive police bonds and never report back to police once they regain their temporary freedom”, Bundibugyo criminal investigations chief, Protus Rutaremwa, says. This has resulted in missed opportunities to hold offenders accountable for their actions.

Rutaremwa says that most of the cases that were prosecuted involved people caught with incriminating evidence such as dead birds or traps.

For those caught empty handed, they give excuses like they were merely passing through the protected area, and the rangers find it difficult to pin them.

Voice of Afande Protus Rutaremwa OC CID Bundibugyo

UWA enforcement staff have also complained of suspects being acquitted by courts of law on grounds that the African green pigeon is not included in the list of protected species. This legal loophole undermines efforts to address community poaching effectively and serves as a hindrance to the enforcement of wildlife protection laws.

According to the amended Uganda Wildlife Act 2019, a person apprehended for offenses not relating to species not classified as extinct in the wild, critically endangered or endangered or offenses under this Act for for which no penalties are provided is charged under general offenses.

In the case of a first offence, such a person is liable to a fine not exceeding 350 currency points or to a term of imprisonment not exceeding 10 years or both.

In the case of a second or subsequent offence, a person is liable to a fine not exceeding 500 currency points or to a term of imprisonment not exceeding 20 years or both.

A currency point is UGX 20,000, meaning that the Semuliki pigeon poachers potentially face fines not exceeding UGX 7,000,000 (USD $1,840) for first offenders and UGX 10,000,000 (USD $2,630) for serial poachers.

Patrick Muzaale, an officer overseeing law enforcement in the Semuliki National Park, says ensuring the safety of park rangers can be life-threatening, as poachers often operate in gangs or groups. In some instances, confrontations occur between the rangers and the poachers, as the latter attempt to escape the scene.

“To further complicate matters, the poachers have adapted their tactics by sending children to engage in illegal activities, hoping to evoke sympathy and evade stringent legal actions,” Muzaale notes.

In response, UWA has taken steps to enhance its staff’s professionalism by deploying new units of investigators embedded within the local communities surrounding the park.

Their goal is to gain an understanding of the poachers’ techniques, motivations, and plans in order to counteract the problem effectively.

Awareness programs are also frequently conducted by UWA in the neighboring areas of the park to educate the local population about the importance of conservation and the need to protect the birds.

Baryesiima says these measures have contributed to a notable recovery in the number of tourists visiting the park from the pandemic slump.

Data compiled by the Uganda Bureau of Statistics and the Uganda Wildlife Authority show that tourist visits to Semuliki topped 30,109 in 2023, the highest number recorded since 2015.

This, Baryiesiima says, is due to the increase in travels to the park by students, tourists from the East African community member states and foreign non-residents, specifically for bird watching.

He says around 20 percent of the revenue collected from the tourists is shared with the communities residing near the park to enhance collaborative conservation efforts.

Need for collaborative action

Francis Nduru, the chairperson local council one for Rwamabaale village in Bundibugyo district, which is known to have a significant number of poachers targeting the green pigeon acknowledges that poaching of the green pigeons now mostly occurs discreetly. He emphasizes the need for people to refrain from entering the park without permission.

Julius Tusiime, the chairperson local council one for Burondo central, highlighted the difficulty of eradicating poaching, as the birds serve as a source of food and livelihood for many individuals.

He suggests that addressing the issue requires a broader approach, including the extension of revenue sharing beyond compensating only those whose crops are destroyed by park animals.

According to Tusiime, poverty is a driving factor behind poaching.

“Many individuals engage in poaching because they lack sustainable income. On a successful day, a poacher can earn a significant amount,” noted Tusiime.

“If the government can support the youth and other individuals through associations and enterprises, this will help to curb poaching by providing alternative means of livelihood,” Tusiime said.

Reliable statistics regarding the scale and scope of pigeon poaching still remain scarce, hindering effective intervention.

Furthermore, there is limited understanding of the detrimental impact of poaching on the social, economic, and cultural significance of these roosting birds.

According to the warden for Semuliki National Park, Godfrey Baryesiima, the plight of the African green pigeons in the National Park is a distressing reminder of the urgent need for collaborative action.

Baryesima says protecting these birds requires a comprehensive approach that involves raising awareness, gathering accurate data, and engaging with local communities to address the underlying issues driving poaching.

He adds that it’s only through these concerted efforts that they can hope to preserve the beauty and diversity of Semuliki’s avian inhabitants for future generations to admire.

This story has been produced in partnership with Info Nile with support from IUCN/TRAFFIC and with funding from JRS Biodiversity Foundation and Earth Journalism Network.